Stolen Future: Part 1

Newer tools provide earlier, more accurate diagnosis for dementia

A swift and accurate diagnosis of dementia affects treatment plans, and access to information and support. Yet a diagnosis is often hard to get.

When symptoms are in the early stages, findings can be unclear, and doctors will monitor patients with appointments six months to a year later. Some cases are complex or atypical, leaving doctors to make their best guess.

That opens the door for misdiagnosis, even among highly trained dementia experts.

Between 10 percent and 35 percent of patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's and referred to studies by specialists did not have the disease, according to a study released in 2015 by a group of international experts.

“The accuracy of clinical diagnosis is probably even lower in the very early clinical stages of the disease,” the study concluded. “This variable and relatively poor performance is particularly troubling given the high level of expertise of the clinicians in the specialized (Alzheimer's disease) centers making the diagnosis, and the diagnostic accuracy in primary or secondary care settings is likely even lower.”

With aging baby boomers expected to more than double the number of dementia cases over the next few decades, experts are calling for a more coordinated approach.

Dementia can be caused by different incurable brain diseases. Alzheimer's is the most common. Each disease progresses differently. A myriad of other issues — ranging from thyroid problems to vitamin deficiencies — can also cause dementia-like symptoms that are reversible.

Specialists mainly rely on verbal and written tests, and interviews with those closest to the patient when diagnosing cognitive impairment or dementia.

Newer diagnostic tools — cerebrospinal fluid analysis or PET scans — can reveal earlier and more accurate answers to what's causing dementia, but they are rarely used beyond research in the U.S. despite studies showing benefits.

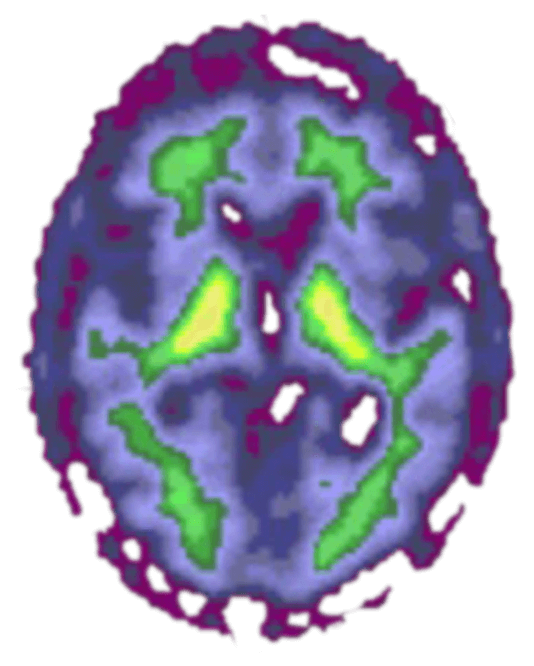

1

Cognitively normal

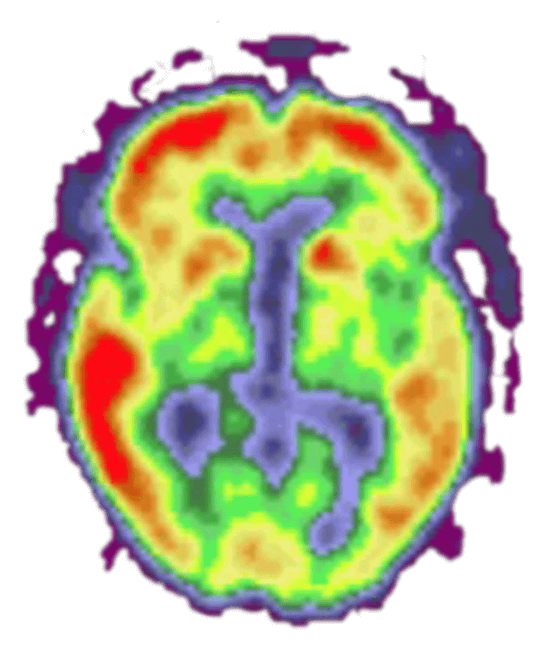

2

Alzheimer's dementia

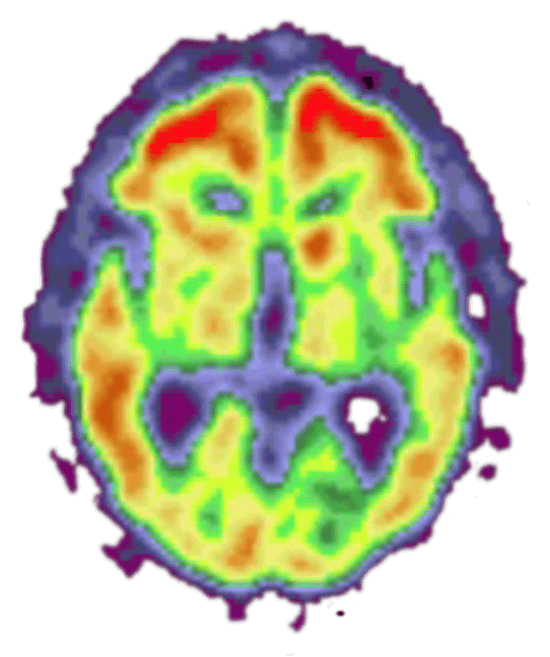

3

Cognitively normal

These PET scans show the brains of three different people. The red and yellow colors indicate high levels of amyloid plaques, a marker of Alzheimer's dementia. 1. The image on the left is of a person with normal cognitive abilities and no amyloid plaques. 2. The middle image is of a person diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. 3. The image on the right is of a person who was cognitively normal at the time of the scan but diagnosed with Alzheimer's dementia three years later. (Provided by Washington University Medical School)

For more than a decade, doctors have been able to draw spinal fluid from a lumbar puncture, also known as a spinal tap, and have it analyzed for proteins that mark Alzheimer's disease. The test is about 90 percent accurate, experts say.

It is not always covered by insurance, however. If it is, it's not reimbursed well for the time it takes to perform, send off for analysis and explain results. Spinal taps can also be seen as invasive, with side effects such as severe headache.

A PET scan, an even newer and more accurate technology for detecting Alzheimer's, is less invasive. It involves injecting molecules into the blood which bind to the telltale proteins and make them visible on a scan. It is not covered by Medicare or private insurance and costs about $4,500.

Ongoing research shows the scans greatly affect management in questionable cases.

Advertisement

The Alzheimer's Association launched an imaging study in 2016 in which Medicare agreed to pay for a PET scan for 18,000 patients with mild cognitive impairment or a questionable dementia diagnosis, referred by their community physician. The study quickly filled.

Preliminary results for 4,000 patients were released last summer. The results were surprising: After the scans, physicians changed medications or recommendations for their patients in two-thirds of the cases.

Diagnoses shifted dramatically, particularly for those who had been wrongly diagnosed with Alzheimer's.

“That is far greater than what was expected,” said Jim Hendrix, director of global science initiatives for the Alzheimer’s Association. “That says a lot about the value of having a tool to help physicians make an accurate diagnosis.”

Researchers are continuing to follow patients in the study to determine whether the management changes make a difference. Some argue that with no cure, getting an accurate diagnosis is not that critical, or even too upsetting for those in early stages.

But new data in the annual Alzheimer's Association report released in March shows diagnosis during the mild stage of the disease would save as much as $7.9 trillion over the lifetime of all Americans currently living with the disease.

“Costs are lower once a person with Alzheimer's gets on the right care path. The disease is better managed, there are fewer complications from other conditions and unnecessary hospitalizations are avoided,” said Keith Fargo, the association's director of scientific programs and outreach.

Other benefits, the annual report said, include allowing individuals to adopt lifestyle changes that can help preserve their cognitive function as long as possible, enroll in research and plan for the future.

It can open the door to support programs and provide people an opportunity to maximize time spent in meaningful activities.

Dr. Norman Foster, director of the University of Utah Center for Alzheimer's Care, Imaging and Research, advocates for more routine use of the technology.

“If you don't know what the cause is, you are just guessing how to treat it; and you are not taking advantage of what we've learned about Alzheimer's disease, what the course is, what the likely complications are, what you need to plan for,” Foster said. “It's so sad.”

Some patients are making major decisions such as moving or quitting their jobs, unsure of their diagnosis or what to expect.

“Patients often endure a diagnostic odyssey of several years. They frequently see multiple doctors to try and get answers and are not directed where to go to get answers,” Foster said. “Physicians tend to deny, delay or defer care to put this off.”

Questions

We're interested in hearing from readers who are living with dementia, or caring for someone with dementia. As with any conversation, keep comments polite and refrain from personal insults, foul language or off-topic remarks.

Read more about our commenting guidelines.

About this series

Michele Munz has been a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for 20 years, the past nine covering health and medicine. As a health reporter, Munz has won awards for her coverage of midwifery care, an experimental treatment for ALS and the opioid epidemic. She was the St. Louis Newspaper Guild’s 2015 Terry Hughes Award winner.

Christian Gooden has been with the Post-Dispatch since 1999. He is a native of University City and graduate of Cardinal Ritter College Preparatory High School. He earned a degree in journalism from Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga. He has worked at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Milledgeville (Georgia) Union-Recorder.

Cristina M. Fletes is a staff photographer and videographer at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. She received a bachelor of fine arts degree in studio art from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and a master's degree in photojournalism from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Andrew Nguyen

Developer

Josh Renaud

Developer

Beth O'Malley

Audience engagement

Elaine Vydra

Audience engagement

Janelle O'Dea

Data reporter

Hillary Levin

Multimedia producer

Gary Hairlson

Multimedia director

Jean Buchanan

Projects editor

Evan Hill

Print designer

Jennie Crabbe

Copy editor

June Heath

Copy editor

Colleen Schrappen

Copy editor