Stolen Future: Part 4

Tight budgets and drained savings

About the series

Lonni Schicker, 64, was always the one to depend on, to get things done and to figure things out. She was the person who took care of others. At least until about five years ago, when Lonni's doctor told her that at age 59 she had mild cognitive impairment. The diagnosis placed her at higher risk of dementia. Lonni quit her job as a professor and moved into an apartment in Fenton with her son. Her problems have since gotten worse. Hoping to help others, Lonni is sharing her story about her frustrating search for a diagnosis and unique challenges when symptoms strike at a younger age.

Listen

Michele Munz reads the fourth story in her series about Lonni Schicker and her struggles with dementia. Lonni and her son are facing the financial toll of her condition as the bills pile up.

Lonni Schicker, 63, sets up her laptop on a small table in the corner of the kitchen of the apartment. The computer is on loan from the Alzheimer's Association. She opens a spreadsheet.

A stack of bills sits between her and her son, Dan Schicker, 32.

“So, what I need, Dan, is the name of the provider, the date of service and the amount due,” Lonni tells him. “And the billing phone number.”

The plan is for him to call each one, ask for discounts and negotiate a payment plan.

When medical bills come in the mail, Dan can't bear to open them. He just adds them to the stack.

The bills are for his mom, whom he's been caring for in their Fenton apartment since memory problems ended her career as a college professor almost five years ago at the age of 59. Her problems have since progressed to dementia.

He pulled the stack from a drawer in the garage, where he doesn't have to look at the bills.

“We struggle enough to pay regular bills,” Dan says. “These, on top of it, is overwhelming.”

Lonni knows the thought of going through the stack paralyzes him. After weeks of excuses, she's finally convinced him to sit down after work one night and go through it together.

Dan rips one open and reads the amount: “BJC Emergency, $270.66.”

With each envelope, he gets angrier.

“It's just knowing the number of them,” Dan said, “and the thought of how poorly you were treated by the government because of your disease.”

When Lonni stopped working, she was approved for Social Security disability, which took six months to begin. She had to wait two years for her disability to be considered permanent and covered under Medicare.

In the interim, she was on Medicaid, which meant going to clinics where she saw a different doctor every time. Each month, she had to pay the first $1,500 out of pocket before any care was covered, she said.

It drained her savings. They fell months behind in rent, utilities, car and student loan payments. “Her health care was more important than any bill,” Dan said.

Her health also suffered. Her diabetes and blood pressure were poorly managed, sending her to the emergency room. She battled depression and anxiety. Her memory problems got worse.

“Clinics are Band-Aids,” Lonni said. “They treat the immediate need, but there's no long-term or follow-up care. There's no treating of the underlying problem.”

Lonni Schicker chats with her nurse D’juana “Dee” Franklin on Friday, Sept. 7, 2018, before getting a bed bath at Mercy Hospital St. Louis as she recovers from a recent back surgery there. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

A year ago, Lonni's Medicare coverage began. She finally had surgery for a painful torn rotator cuff. She began regular visits with an internist to stabilize her blood sugar, a psychiatrist to treat her anxiety and a neurosurgeon to manage her dementia.

Dan says, “Part of it is a spite issue. I don't want to pay it. (Expletive), you didn't take care of my mom.”

Advertisement

Check to check

Lonni Schicker, 63, describes the devastating effects that dementia has had on her finances. Once making a six-figure salary, she now lives month-to-month on disability checks. With mounting medical bills and scant medical insurance coverage, Lonni has not only run through her savings, but through her son's as well. (Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

The financial toll of Alzheimer's and related dementias on families is staggering. Figures show that dementia caregivers, often a spouse or child, spend an average of $10,700 a year — nearly twice that of caregivers for those with other conditions.

A 2015 study of Medicare patients found that the out-of-pocket cost for a dementia patient in the last five years of life was $61,522, more than 80 percent higher than the cost for someone suffering from other leading killers like heart disease or cancer.

“Some consider or actually go through a divorce from their spouse with dementia to try to preserve assets out of fear of financial destitution.”

Many of the costs associated with dementia care do not involve surgeries or treatments. They include deductibles and copayments and what can be many years of help in the home with eating, grooming and bathing — which are not covered by Medicare.

People in moderate stages of dementia benefit immensely from socialization and meaningful activities, but Medicare doesn't cover adult day care programs.

Preparing healthy meals, forgetting to eat and incontinence are problems, but Medicare doesn't cover nutritional supplements or adult diapers.

Cheryl Kinney, director of client services with the Alzheimer's Association Greater Missouri Chapter, said families are struggling.

“Unless an individual purchased long-term care insurance before the dementia diagnosis, medical insurance doesn't cover expenses such as in-home support to provide supervision, oversight and companionship,” Kinney said. “Many individuals with Alzheimer's don't have a need for nursing visits, but they do need someone to assure they are safe at home.”

Listen

Debra Schuster, an elder law attorney in Clayton, discusses the financial impact of dementia and how to best prepare and handle the challenges.

Harder to measure are the ripple effects. When younger adults are diagnosed with dementia while they are still working, they often have to quit their jobs. Families with children at home end up scrapping college saving plans.

Adult children may have to quit their jobs to become caregivers, which makes it harder for them to re-enter the workforce later and decimates their savings.

“Some have to turn to public assistance such as food stamps to make ends meet. Some cash in their investments and tap into their retirement benefits in order to cover daily living expenses,” Kinney said. “Some consider or actually go through a divorce from their spouse with dementia to try to preserve assets out of fear of financial destitution.”

The strain leads to anxiety, shame, depression and social isolation. For patients, this can also exacerbate symptoms of dementia.

When Lonni first started experiencing problems as a professor five years ago, she was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. About 16 percent of people age 60 and over in the U.S. — 11.6 million people — have the impairment. Studies estimate almost 40 percent will develop dementia, when symptoms become severe enough to interfere with daily function.

Lonni was diagnosed with dementia earlier this year, and her neurosurgeon is monitoring her for a progressive form known as Lewy Body dementia. Like Alzheimer's, there is no cure.

“I have nothing left,” Lonni said. “I have no assets, no savings, no retirement funds left. I'm living from disability check to disability check.”

Advertisement

Keeping it private

Dan Schicker (center), 31, plays Dungeons and Dragons with friends Tim Cox (left), 28, of House Springs, and Brandon Bardenheier, 30, of Fenton, in the garage of the apartment in Fenton he shares with his mom, Lonni, on Sunday, Feb. 11, 2018. Dan later sold his gaming equipment to help pay bills as he and his mother struggled with financial issues brought on by her dementia. Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Their small two-bedroom apartment came with a perk — a one-car garage. Dan used it as his “man cave,” outfitting it with secondhand furniture, a wall-size television screen and a projector.

After work and caring for his mom, Dan spent nights there with friends, eating spaghetti Lonni made, playing Dungeons and Dragons and watching football games.

One night, he sold it all.

That month, Dan was late on paying rent and other bills, but he shrugged it off as having nothing to do with that. “I didn't need it,” he said.

Stress and anxiety make his mom's symptoms worse. He has taken over the finances, so he tries to shield her from problems as much as possible.

“I'd rather me be stressed than her,” Dan said. “I've sold my game systems more times than I can count. I'll sell some furniture. I'll just do what I can to make it.”

But that is getting harder. He used all his vacation days to either take his mom to doctor's appointments or to be with her when she was having a hard day. “So days I have to take off when she is sick, I don't get paid for it,” he said.

Dan says it's critical for his mom to get out, socialize and stay active. She works at home part time, entering information for a church directory into spreadsheets.

Lonni Schicker, 63, of Fenton, shops at Savers Thrift Store in Crestwood on Wednesday, July 25, 2018. Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“I'd rather me be stressed than her. I've sold my game systems more times than I can count. I'll sell some furniture. I'll just do what I can to make it.”

When she wants to play bingo or have lunch with friends, he doesn't want to tell her no. He thinks about what they can sacrifice — groceries? Paying a bill late? — so she's not cooped up.

“I don't want to dictate how she spends the rest of her life. I want her to be happy,” he said. “She hates being at home. She's always been the type of person that has to be doing something.”

While Lonni copes by speaking out about her struggles as a volunteer and advocate with the Alzheimer's Association, Dan is more private.

“The idea that this is in an article makes me so uncomfortable,” he said. “I don't want people to know. My friends don't even know how serious this is.”

He hides his worry with his wicked sense of humor. He tries to put the bills out of sight and out of mind. “I don't like asking for money; it's hard for me to ask for help,” he said. “I usually just ignore it.”

But Lonni can sense the stress. She knows Dan is constantly worried about money. She hates that he has to take care of her and make sacrifices with his own money and social life.

While staying busy keeps her happy, it has become harder to get out with a tight budget. In the spring, she stopped driving because it became too dangerous.

In early May, for the second time in the past four years, Lonni's depression got so bad she had to stay in the hospital for a few days. She had been losing her balance and having painful falls. A new medication was not reacting well with another.

“I just felt like I was done with everything. It's OK if I just die. I don't really care,” Lonni recalled thinking. “I'm just done with all this.”

When she went to see her psychiatrist, a $40 copay sent her over the edge. She had no money with her. She called Dan, sobbing. “Don't waste your money on me,” he recalled her saying. “I'm worthless.”

“I just felt like I was done with everything. It's OK if I just die. I don't really care. I'm just done with all this."

Dan talked her into staying. The psychiatrist was so concerned, she told Lonni's friend who had driven her there to take her straight to the hospital.

“I was in a state where I didn't want to spend the money,” Lonni said. “I thought, it's not going to help anyway. I thought things were never going to get better.”

Advertisement

Who can afford this?

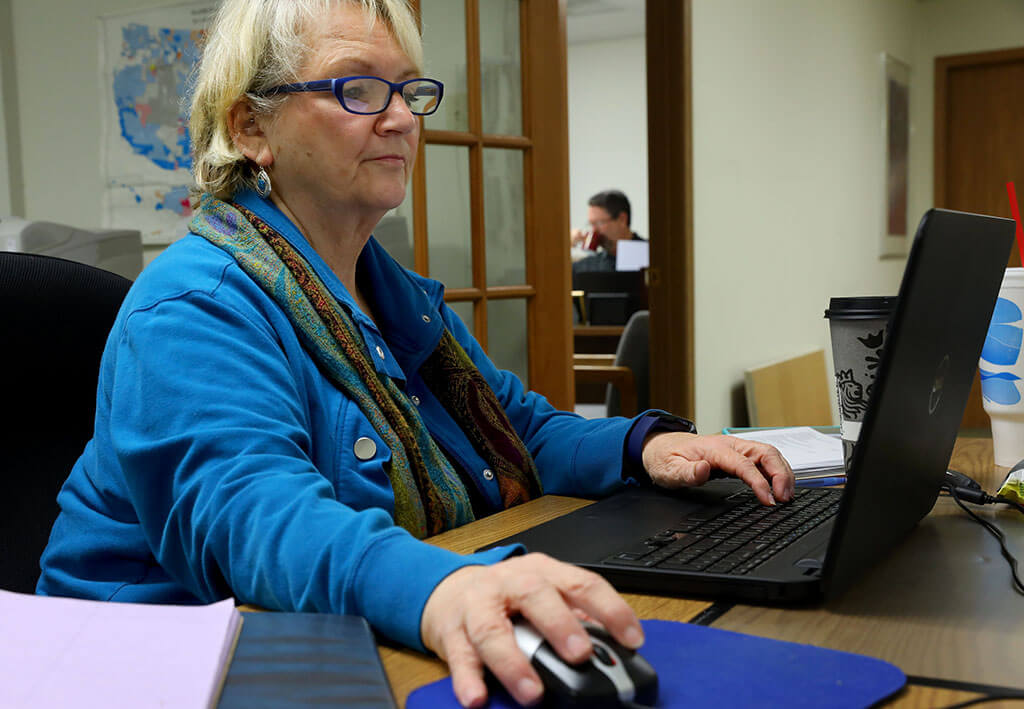

Lonni Schicker works at her part-time job researching churches for Guide Book Publishing in Ballwin. She has had to quit driving and now works from home. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Lonni always worked long days, doing whatever she had to do as a single mom to take care of her son. While working as a nurse's aide, she earned her nursing degree. While working as a nurse and in health care administration, she earned her bachelor's, master's and doctorate degrees.

She had just gotten her dream job as a professor when her memory problems started.

“I didn't save much,” Lonni said. “I thought I would die at my desk.”

When Lonni applied for disability, she had no idea what little would be covered.

“They don't tell you that you will be on Medicaid for two years with a $1,500 spend-down you have to pay out-of-pocket,” Lonni said. “No one tells you anything to prepare you.”

Debra Schuster, a lawyer in Clayton who specializes in elder law, helps families navigate the confusing world of insurance coverage, estates and trusts to protect assets — all while helping them deal with issues such as power of attorney, financial exploitation and end-of-life care.

She connects families to programs that help cover the costs of needs such as adult day care and transportation.

“Most of the time, people are not as proactive as they could be because they don't know this area of law exists,” Schuster said.

Many are unaware Medicare — the federal health insurance program for those over age 65 — does not cover assisted living or long-term skilled nursing home care, she said. It only covers skilled care for a few months after a hospital stay.

Medicaid, the federal program for the poor and disabled, covers nursing home care after income and savings are exhausted. It pays a small portion of assisted living only in limited circumstances.

“Studies show people do better in their home, particularly people with dementia, but there's a real disincentive from a policy standpoint for people to stay in their homes. There's not enough financial support,” Schuster said. “Medicaid provides more financial support for people to go into nursing homes.”

Long-term health insurance is just as important as homeowners or auto insurance, she said. “Really, the biggest issue for people is to invest in some form of long-term care insurance before they become ill."

Long-term care insurance typically covers the cost of care in a nursing home, assisted living facility and dementia facility, as well as services such as adult day care and support in the home.

Long-term care policies are more affordable when you buy them in your 50s, but prices are rising and benefits are becoming more limited. A financial adviser or elder law attorney can help determine what policy is best considering savings, health, family history, availability of family caregivers and personal wishes.

John Beuerlein, the Edward Jones principal who leads the investment firm's Older Adult Council, says life insurance policies with chronic health care riders are becoming more popular than expensive long-term health care plans.

“I tell people to consider their employer coverage options for disability coverage or long-term care coverage,” Beuerlein said. “There are private policies, but they are very expensive. Many are rolling the dice and saying, 'I'll take my chances.'”

In March, Lonni toured an assisted-living facility. She was worried about her frequent falls, her strange hallucinations and feeling lonely. She was also concerned about Dan, who worries about her being home alone.

The price tag was $7,000 a month.

Lonni Schicker (center) and her friend Susan Miller listen as Janis McGillick gives a personal tour of the grounds of Dolan Memory Care Home on Friday, March 23, 2018, in west St. Louis County. McGillick is the director of community engagement for the company that runs the home. Lonni wanted to see what kinds of facilities were available and how much they cost. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Lonni Schicker (center) listens as Janis McGillick (left) goes over assisted living housing costs in the Seniors' Resource guide on Friday, March 23, 2018, at Dolan Memory Care Home in west St. Louis County. McGillick is the director of community engagement for the company that runs Dolan. Lonni, accompanied by her friend Susan Miller (right), met for a tour. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“It was eye-opening. It was really eye-opening. I knew it would be expensive, but who can afford this?”

She looked through a book at cheaper options, but they were still costly. Figures from this year's Alzheimer's Association report show the median cost for care in an assisted living facility is $3,750 a month.

“It was eye-opening. It was really eye-opening,” Lonni said. “I knew it would be expensive, but who can afford this?”

She hasn't pursued any more options since, despite fracturing a rib and a bone in her lower back from falls at home. The last fall required extensive back surgery.

Advertisement

The downfall

After Dan rips through the last bill, Lonni reads the tally: “So Dan, we owe $7,283.66."

That doesn't count money they owe for taxes, credit card bills and previous medical bills. Calculating in her head, Lonni says, “Our overall debt is probably about $13,000."

Those with Alzheimer’s or other dementia are more likely than those without dementia to have other chronic conditions such as coronary artery disease, diabetes, kidney disease and congestive heart failure, studies show.

When a person is diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or early stages of dementia, advocates say coordinated care among specialists would better manage medical conditions and preserve brain function for as long as possible.

Medicare beneficiaries 65 or older with dementia and coexisting conditions

From a sample of Medicare beneficiaries for 2013 and Alzheimer's Association. Total is more than 100 because some people have multiple conditions.

| Coexisting condition | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Coronary artery disease | 38 |

| Diabetes | 37 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 29 |

| Congestive heart failure | 28 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25 |

| Stroke | 22 |

| Cancer | 13 |

Lonni Schicker tries out a scooter with service technician Chris Puleo (left), as she shops with Dan at Provider Plus Inc. on Friday, August 3, 2018. The scooter could help her avoid falls, which have recently led to injuries. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

For nearly three years, however, Lonni got piecemeal care that sent her into debt and exacerbated her health problems.

“That was the start of the downfall,” her son said.

Dan recently found a higher-paying job at an IT and communications services company. In October, he'll earn some vacation days.

He hopes to be able to schedule a surgery for himself he's had to put off. He hopes to start paying down their debt. He wants to make his mom happy.

“Now, I feel like I can save some money, save for when she needs assisted-living some day,” he said. "And maybe a house. I want a house.”

Fact box

Ten tips to prepare for the cost of care

- Talk about finances and future care wishes soon after a diagnosis.

- Organize and review important documents.

- Get help from well-qualified financial and legal advisers.

- Estimate possible costs for the entire disease process.

- Look at all of your insurance options.

- Consider work-related salary/benefits and personal property as potential income.

- Find out which government programs you are eligible for.

- Learn about income tax breaks you may qualify for.

- Explore financial assistance you can personally provide.

- Take advantage of low-cost and free community services.

Average costs of long-term care

Most families pay for residential care costs out of their own pockets. Medicare covers short-term skilled care only after a hospital stay. Medicaid pays for nursing home and other long-term care services for some people with very low income and fewer assets.

- Nonmedical home health aide: $22 an hour and $135 a day

- Adult day care services: $70 a day

- Assisted living facilities: $3,750 a month, or $45,000 a year

- Nursing homes: A private room is $267 a day, or $97,455 a year. A semi-private room in a nursing home is $235 a day, or $85,775 a year

How to find a financial adviser or elder law attorney

- Visit the Eldercare Locator online or call 1-800-677-1116.

- Use the online directory of the Financial Planning Association or call 1-800-322-4237.

- Use the online directory of the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys.

When selecting a financial adviser, check qualifications such as:

- Professional credentials

- Work experience

- Educational background

- Membership in professional associations

- Areas of specialty

How to find help with care

- The National Association of Agencies on Aging is a national nonprofit network of 622 local groups offering a wide array of services, including senior centers, meal programs, adult day care, transportation, legal help, and in-home and respite care.

- To learn more about services in St. Louis, St. Charles, Jefferson and Franklin counties, visit the Mid-East Area Agency on Aging at agingmissouri.org. In the city of St. Louis, visit the St. Louis Area Agency on Aging at slaaa.org.

- A complete list of agencies across Missouri can be found at the Missouri Association of Area Agencies on Aging at ma4web.org. For the Illinois Area Agencies on Aging, visit illinois.gov/aging.

- If you suspect a senior or disabled adult is being abused, bullied, neglected or financially exploited in Missouri, call the abuse hotline 1-800-392-0210, available daily from 7 a.m. to midnight. In Illinois, the hotline can be reached 24 hours a day at 1-866-800-1409.

Source: Alzheimer's Association

Questions

We're interested in hearing from readers who are living with dementia, or caring for someone with dementia. As with any conversation, keep comments polite and refrain from personal insults, foul language or off-topic remarks.

Read more about our commenting guidelines.

About this series

Michele Munz has been a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for 20 years, the past nine covering health and medicine. As a health reporter, Munz has won awards for her coverage of midwifery care, an experimental treatment for ALS and the opioid epidemic. She was the St. Louis Newspaper Guild’s 2015 Terry Hughes Award winner.

Christian Gooden has been with the Post-Dispatch since 1999. He is a native of University City and graduate of Cardinal Ritter College Preparatory High School. He earned a degree in journalism from Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga. He has worked at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Milledgeville (Georgia) Union-Recorder.

Cristina M. Fletes is a staff photographer and videographer at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. She received a bachelor of fine arts degree in studio art from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and a master's degree in photojournalism from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Andrew Nguyen

Developer

Josh Renaud

Developer

Beth O'Malley

Audience engagement

Elaine Vydra

Audience engagement

Janelle O'Dea

Data reporter

Hillary Levin

Multimedia producer

Gary Hairlson

Multimedia director

Jean Buchanan

Projects editor

Evan Hill

Print designer

Jennie Crabbe

Copy editor

June Heath

Copy editor

Colleen Schrappen

Copy editor