Stolen Future: Part 2

Some answers, but more questions

About the series

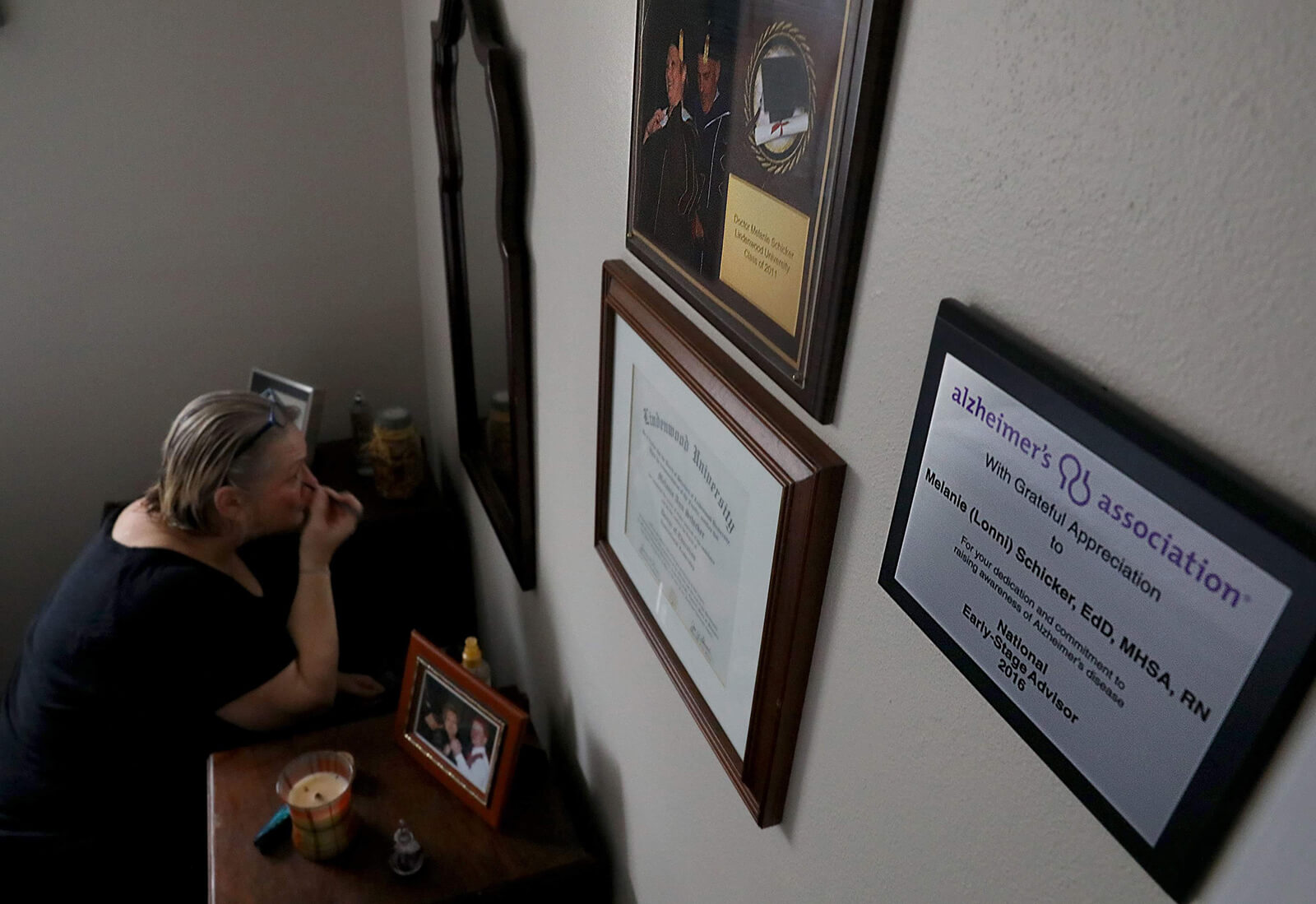

Lonni Schicker, 64, was always the one to depend on, to get things done and to figure things out. She was the person who took care of others. At least until about five years ago, when Lonni's doctor told her that at age 59 she had mild cognitive impairment. The diagnosis placed her at higher risk of dementia. Lonni quit her job as a professor and moved into an apartment in Fenton with her son. Her problems have since gotten worse. Hoping to help others, Lonni is sharing her story about her frustrating search for a diagnosis and unique challenges when symptoms strike at a younger age.

Listen

Michele Munz reads the second story in her series about Lonni Schicker and her struggles with dementia. Lonni learns that her condition has progressed to dementia but there are questions about the cause.

The neurologist asked Melanie “Lonni” Schicker to count backward from 100 by 7. With long pauses, and counting under her breath, she answered: 93, 86, 79, 52, 53, 36.

Lonni was at Mercy Hospital St. Louis in April undergoing testing for dementia with Dr. Mohamed Babiker Tom Bakhit, who goes by Dr. Tom.

Tom had reviewed her extensive neuropsychological testing — mostly pen and paper quizzes and questions — which she had completed the previous month. But he was making some of his own observations.

Lonni, 63, has been seeking a diagnosis since her thinking abilities started to decline in 2014 and she became among the millions of Americans diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, which can often lead to dementia. She ended her career as a professor and moved to an apartment with her son Dan, 32, in Fenton.

Her problems have worsened since then, especially over the past few months, and she was hoping to finally find out why.

Lonni Schicker's whole life has changed since the first noticeable symptoms of dementia began five years ago, at the age of 58. A former professor, she quit her job after feeling she could no longer offer students her best. She now lives with her son and is learning to cope with the effects of a disease that is eroding her most precious attribute — her mind. (Cristina M. Fletes)

Tom asked her to touch her thumb to each finger. She did so very slowly despite his command to go faster. Her hands trembled when she held them out.

She told Tom about her falls. And that she's seeing things — like animals — she knows aren't there.

Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia, but there are other lesser-known causes. They may differ in how symptoms progress, but they have the same devastating ending: total loss of brain function.

Lonni wants to know why her brain doesn't work anymore.

She needs to prepare. She needs to plan. She wants what she has to have a name.

Tom concluded that Lonni has progressed to dementia — when decline in thinking becomes severe enough to interfere with daily life — but questions remain.

She shows symptoms of Lewy body dementia, the second-most common form of dementia, he told her. Protein deposits, called Lewy bodies, develop in nerve cells in the brain regions involved in thinking, memory and movement.

But Tom stopped short of diagnosing her with the disease because she did well on her neuropsychological tests. So well, he was able to rule out Alzheimer's, which would have progressed differently. Her anxiety and depression also could play a role.

He wants to monitor her symptoms and see her again in September.

“A lot of time, that is the case. A lot of time, it's difficult to have a definitive diagnosis, especially when it's in the early stages of process,” Tom said. “I don't want to jump to any conclusions.”

Advertisement

‘Breaking down’

The journey to a diagnosis is often long and frustrating, advocates say, especially for those who begin to notice their cognitive impairments before they turn 65, or in the early stages, when dementia is not on the radar or symptoms are not typical.

A report by the Alzheimer's Association found that some people wait as long as six years for a dementia diagnosis, and some receive one or more wrong diagnoses before finally learning they have dementia.

“While we now have very good methods for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease in patients, there are many other causes of memory impairment, some of which can be difficult to diagnose.”

Some doctors may not feel confident in diagnosing younger-onset dementia because a myriad of other issues — from hormone imbalances to vitamin deficiencies — can cause dementia-like symptoms.

“While we now have very good methods for diagnosing Alzheimer's disease in patients, there are many other causes of memory impairment, some of which can be difficult to diagnose,” said Dr. Erik Musiek, neurologist and researcher at Washington University School of Medicine. “Some people have memory changes which do not fall cleanly into defined categories, which can lead to a lot of negative testing that can be frustrating for patients and doctors.”

Dan says when he and his mom first moved in together more than four years ago, she seemed to struggle just 10 percent of the time.

“The last 1½ years, it's progressing faster, to where it's 60-40, maybe even 50-50, where she just isn't functioning like a normal adult,” he said. “She's forgetting to do things, breaking down for no reason and just … getting upset.”

Tom asked Lonni to remember three words: season, leader and table. After several simple questions, he asked her to recall the words. She struggled for a long 15 seconds. She looked like she was about to cry.

It starts with an “s,” Tom reminded her.

“Salt?” she said.

Dr. Mohamed Tom, a neurologist at Mercy Hospital, explains why dementia is difficult to diagnose - from its slow progression to its mimicking of other health conditions. (Cristina M. Fletes)

Advertisement

From that, to nothing

Lonni wants an answer, but an answer isn't stopping the changes. She knows she's not the person she was. And lately, the changes have been coming fast.

“She's forgetting to do things, breaking down for no reason and just … getting upset.”

In early spring, she was on a familiar road in the middle of the day when she made a turn and ended up driving onto a concrete median.

She had been using the OnStar navigation system to guide her everywhere she went, even to her usual grocery store. But there were times when she felt unsure of her surroundings or overly upset by other drivers.

She decided to stop driving, leaving her feeling trapped in her apartment.

Nights of grading papers, preparing lesson plans and meeting with students have been replaced with watching television with Dan from their recliners. But even that is getting stressful.

Lonni forgets plot lines from a season of episodes they just finished watching a few days earlier, Dan said. If a show jumps back and forth, she gets confused.

“Oh they are back together!” she'll say about an estranged couple during a flashback.

Dan tries to remind her. He tries to explain. But eventually, he gets frustrated and gives up. “I just stop correcting her,” he said. “I just won't say anything.”

Lonni senses when this happens. She tries not to let it hurt her feelings.

“He's been pretty impatient with me lately,” she said. “I think he kind of ignores me when I ask him something. I ask him questions, and then suddenly he is not answering. But I would be frustrated, too.”

It's hard. Lonni used to be the person everyone went to for answers.

She was tapped to write the master's program in health administration at Minnesota State University, advised 120 students and was a mentor to many. She worked as a nurse and in health care management, all the while raising a child, working toward her doctorate, and being the matriarch and planner for extended family.

Lonni Schicker gets ready to leave for a trip to the office of Guide Book Publishing on Friday, Feb. 23, 2018, in Ballwin. Although she usually works from home, she sometimes goes in to the office to do her searches and to touch base with her boss. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Her bosses praised her on the LinkedIn professional networking site as someone with excellent analytical skills and attention to detail.

“Her dedication to ensuring quality outcomes, ability to manage her time effectively while multi-tasking various assignments, and remaining results-oriented to meet margins was commendable,” wrote her manager at Centene Corporation.

Now her weeks are spent working a part-time job, looking up information about churches for a company that publishes church directories. It takes two hours for her to put the information into a spreadsheet, a task that would have taken her 30 minutes just a few years ago.

She's never been “artsy,” she said, but she makes earrings, and knits hats and blankets. She cleans obsessively.

She can't stand being idle, being alone. All her life, when depression threatened, she buried herself in work, but that is harder now. “I was always incredibly busy,” she said, “and I went from that, to nothing.”

“He's been pretty impatient with me lately. I think he kind of ignores me when I ask him something. I ask him questions, and then suddenly he is not answering. But I would be frustrated, too.”

Lonni used to make a list of what she needed to do the next day. She liked to plan, know what to expect. But dementia makes life uncertain.

Her lists, notes on the calendar and cell phone alarms helped her navigate her days as her thinking declined. But lately, those reminders don't even make sense, nor do the emails or texts she keeps as background.

During one of her last trips driving to the grocery store, she zigzagged among the aisles, pausing to ponder the overwhelming choices of cheese or hot dogs. She passed a display of candy on sale and grabbed her favorite, Sprees, only to realize she already had a box in her cart.

She used to zip strategically through a store. Cooking was fun and easy. Now planning and preparing a meal feels like a major undertaking.

Lonni Schicker pauses a moment to think as she shops at the Aldi near her home in Fenton on Friday, March 9, 2018. Lonni finds it harder to do everyday chores without constantly making lists. She says it is taking her longer to gather each item on her list, which she keeps on her phone. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“It's like a full-time job, where it used to be an ancillary part of the day,” she said. “It's frustrating for someone who has always been so methodical and meticulous.”

Advertisement

Feeling like a nobody

Lonni finds herself reminiscing more about the past.

Driving through the winding roads of the Bayshore subdivision in Arnold where she grew up, Lonni shared stories of those who used to live in the small homes — her best friend, the sheriff, her first boyfriend, a firefighter. “He got my dad a job at the fire house as a dispatcher,” she said. “My dad worked there 30 years.”

She pointed out where a malt shop and go-kart track used to be, the orchard where she picked apples in the summer. Twin Pools had a way better concession stand than her neighborhood pool. They played in the Meramec River when they weren't supposed to and had to make sure they returned with no ticks.

“It's funny,” Lonni said. “Now I talk about my childhood all the time.”

Those years are easy to recall. It's the recent days and years where details are fuzzy. She feels more confused. She compares the feeling to waking up from a nap not knowing what day or time it is.

“Sometimes that just happens when I'm in the middle of something. It's like, I know where I am, but I don't know what I'm supposed to be doing,” she said. “I feel like I'm supposed to be doing something else.”

She's scared. Her identity has been her intelligence, and she feels it slipping away. “I'm worried about feeling like a nobody,” she said.

Dan has learned meltdowns are inevitable.

“She gets into super-panic mode over stuff not necessarily urgent. If something is wrong, it's as-bad-as-it-can-get wrong.”

Three times a day she scrubbed at a white film on the dark wood laminate floors in their apartment, trying different cleaning solutions. But the floors kept getting cloudier.

“The landlord is going to make me pay for the floors,” she said, crying. “I'm a failure. I can't do anything right.”

An impatient salesperson leaves her sobbing in the car. A misplaced work folder has her convinced she'll be fired. A minor disagreement with her sister has her threatening to cancel a trip to visit.

Dan said she was always thick-skinned, unflappable. Now, he constantly has to calm and reassure her.

“She gets into super-panic mode over stuff not necessarily urgent,” he said. “If something is wrong, it's as-bad-as-it-can-get wrong.”

Lonni's younger sister, Mary Allen, 59, lives in the Las Vegas area. Growing up, she remembers telling Lonni, "You aren't the boss of me." But Allen came to depend on her big sister's advice. She misses being able to lean on Lonni.

“It's kind of like when your parents get older, you become like the parent and they become the child,” she said. “Well, now I've become the big sister.”

Advertisement

A care team

Lonni, five of her closest friends, Dan and his best friend gathered around a table in March on the back patio of Seamus McDaniel's, a busy pub in Dogtown where Lonni grew up celebrating family milestones like birthdays and graduations.

The group met for an early dinner at the suggestion of Rebekah Backowski, 43, who worked with Lonni 10 years ago as a review nurse for the then-Mercy Health Plans. “Do you know I don't know any of your friends?” Backowski had told Lonni. “What if you need something, and I can't be there? I'd like to have someone I can call.”

As they looked over menus and ordered drinks, Backowski passed around a paper for everyone to write down their names, numbers and emails.

They tried to figure out who had known Lonni the longest. It was June McCartney, 60, of Fenton, who met Lonni in 1979 while working together in the burn unit at Mercy Hospital St. Louis.

Lonni held her hands together to keep them from shaking — a new symptom — and filled them all in on the latest:

She has stopped driving. She senses things that aren't there, like her old dog or someone staring at her through the window. She's been falling … a lot.

“The whole time Dan is at work, he's worried about me falling and seeing things. So, we've been talking about what I'm going to do all by myself at home every day.”

Physical therapist Derek Gould prepares Lonni Schicker for an exercise during her first physical therapy appointment on Wednesday, April 25, 2018. Lonni has been falling frequently and the physical therapy is to improve her motor skills. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

She falls reaching for dishes or turning away from the washing machine. She runs into door jams. She trips over something she thinks she sees on the floor, like a cord.

She went to a doctor for pain in her side, and it turned out to be a fractured rib. She's not sure how she did it.

"The whole time Dan is at work, he's worried about me falling and seeing things," Lonni told them. "So, we've been talking about what I'm going to do all by myself at home every day. I don't get any socialization during the day. All my friends work."

The next day, she revealed, she was going to check out Dolan Memory Care Homes, a household model designed to assist about a dozen residents through the end of life. She wasn't sure whether she could afford it.

Surprised, they asked how soon she could be moving.

“Probably sooner than later,” Lonni said. She doesn't want to face a long wait list when her situation is more dire, she said. “It's so hard to get in.”

To help keep her safe in the meantime, Tom prescribed Lonni a medication typically given to Parkinson's patients to help with her motor control. He also prescribed physical therapy and assessment for a cane or walker, as well as vigorous exercise and healthy food.

The hardest is not being able to drive. Lonni feels cooped up. She lives at the end of a hilly cul de sac leading to a winding two-lane road with no sidewalks, so she can't even go on a walk.

She and Dan say their friends are critical in helping them cope.

When Lonni's sister moved to Las Vegas last summer, Lonni turned to Susan Miller, who was one of her sister's friends, and asked, “Who is going to take care of me?”

Lonni Schicker (left) has lunch with her friend Susan Miller at Joe Clark's Restaurant in Fenton on Wednesday, Feb. 21, 2018. Since returning to St. Louis after her initial diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, Lonni has just a handful of friends she relies on for companionship and favors. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“I will,” Miller said.

Miller, 63 and retired, has become one of Lonni's best friends. She often drives from Belleville to take Lonni to appointments, have lunch or go thrift shopping.

Sometimes, Lonni tells her she doesn't need to come. But Miller ignores that.

There are times, however, when Lonni can't help but feel alone.

One morning, she really wanted a soda. But she couldn't just hop in the car. And it would be silly to ask Miller to drive all the way to Fenton just to bring her a soda.

Lonni suddenly found herself crying.

“The soda wasn't the problem,” she said. “It was the realization that I'm not independent anymore.”

Lonni Schicker keeps her medication box, photographed on Friday, Feb 23, 2018, close to where she spends a lot of time, near the living room couch where Dan Schicker and Harry also often hang out. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Fact box

Lewy body dementia

Lewy body dementia affects an estimated 1.4 million individuals and their families in the U.S. It is a progressive brain disorder in which protein deposits called Lewy bodies build up in areas of the brain that regulate behavior, cognition and movement.

Symptoms include:

- Changes in thinking and reasoning

- Confusion and alertness that varies significantly from one time of day to another or from one day to the next

- Parkinson's symptoms, such as a hunched posture, balance problems and rigid muscles

- Visual hallucinations

- Delusions

- Trouble interpreting visual information

- Acting out dreams, sometimes violently, a problem known as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep disorder

- Malfunctions of the “automatic” (autonomic) nervous system such as blood pressure and bladder control

- Memory loss that may be significant but less prominent than in Alzheimer's

Source: Lewy Body Dementia Association and the Alzheimer's Association

Questions

We're interested in hearing from readers who are living with dementia, or caring for someone with dementia. As with any conversation, keep comments polite and refrain from personal insults, foul language or off-topic remarks.

Read more about our commenting guidelines.

About this series

Michele Munz has been a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for 20 years, the past nine covering health and medicine. As a health reporter, Munz has won awards for her coverage of midwifery care, an experimental treatment for ALS and the opioid epidemic. She was the St. Louis Newspaper Guild’s 2015 Terry Hughes Award winner.

Christian Gooden has been with the Post-Dispatch since 1999. He is a native of University City and graduate of Cardinal Ritter College Preparatory High School. He earned a degree in journalism from Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga. He has worked at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Milledgeville (Georgia) Union-Recorder.

Cristina M. Fletes is a staff photographer and videographer at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. She received a bachelor of fine arts degree in studio art from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and a master's degree in photojournalism from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Andrew Nguyen

Developer

Josh Renaud

Developer

Beth O'Malley

Audience engagement

Elaine Vydra

Audience engagement

Janelle O'Dea

Data reporter

Hillary Levin

Multimedia producer

Gary Hairlson

Multimedia director

Jean Buchanan

Projects editor

Evan Hill

Print designer

Jennie Crabbe

Copy editor

June Heath

Copy editor

Colleen Schrappen

Copy editor