Stolen Future: Part 6

The heartbreak of a long goodbye

About the series

Lonni Schicker, 64, was always the one to depend on, to get things done and to figure things out. She was the person who took care of others. At least until about five years ago, when Lonni's doctor told her that at age 59 she had mild cognitive impairment. The diagnosis placed her at higher risk of dementia. Lonni quit her job as a professor and moved into an apartment in Fenton with her son. Her problems have since gotten worse. Hoping to help others, Lonni is sharing her story about her frustrating search for a diagnosis and unique challenges when symptoms strike at a younger age.

Listen

Michele Munz reads the final story in her series about Lonni Schicker and her struggles with dementia. Here she profiles other families coping with their loved one's memory issues.

Mary Nicoletti, 66, walks through the locked double doors of one of the dementia wings at the skilled nursing facility where her husband lives. She spots him standing at the end of the long hallway, just a thin silhouette against a wide, sunny window.

“Hey Ronnie! Hi!” she yells. Ron Nicoletti, 68, stares but doesn't move.

“Do you see me yet?” Mary says. She waves excitedly, walking closer.

Ron finally responds to her, as if she was just getting off an airplane after years away. They've been married 45 years, but he no longer knows her name.

“Ahhhhhh,” he bellows, coming toward her. She opens her arms for a hug, and he walks into her embrace.

“I love you!” she tells him.

“Love you!” he blurts.

He babbles incoherently. The 1965 hit song “California Girls” blasts though the open door of his room, and he starts to bounce and sway to the music. His five sons made him a digital playlist from the 1960s which nurses can play throughout the day as he wanders the halls.

“He loves to dance,” Mary says.

She notices Ron is holding a red, shiny ball. “Oh you took an ornament, you stinker!” she says. He doesn't notice as she takes it from him and walks around the corner to put it back on a Christmas tree.

Mary holds his hand and leads him out the doors for a walk, but a nurse assistant stops her. “Sorry I'm late,” she tells Mary.

Mary knows she's come to change Ron's diaper. The assistant leads him to his bathroom. His wails can be heard from the hallway. “He hates it,” Mary says.

An undated photo of Ron and Mary Nicoletti as seen on Thursday, Dec. 13, 2018. Mary believes it was taken between 2012 and 2014. Ron was diagnosed with Alzheimer's eight years ago and the disease has progressed significantly. Two years ago, Mary had to place Ron in a facility when she could no longer care for him at home. Photo courtesy of the Nicoletti family

Ron has been in a facility for the past two years. Before that, Mary was taking care of him, trying her best to keep him safe, clean and happy. It was becoming impossible. “One day, he said, 'Plan B. Plan B. Plan B,” Mary recalls.

They were fighting. She had become less of a wife and more of a nurse, checking off her daily duties. “He hated it,” she says. “It was his dignity.”

The assistant returns with Ron. “There's your beautiful wife,” she says, as she hands him over to Mary.

“I believe it,” Ron says, making everyone laugh.

They are the only decipherable words he manages for the rest of their visit that day.

Advertisement

We all have stories

Statistics show how dementia and Alzheimer's disease are affecting families across the country. Every 65 seconds, someone in in the U.S. develops Alzheimer's, the most common cause of dementia. That amounts to 5.7 million people.

Over the next six years, the number is projected to jump to 7.1 million as baby boomers get older.

In Missouri, more than 110,000 people over the age of 65 have Alzheimer's disease. By 2025, the number will be 130,000.

For every person with the disease, an average of three people take on caregiving duties — a spouse, child, sibling, friend or relative.

Alzheimer's is the most expensive disease in the country, costing an estimated $277 billion this year — including $186 billion in direct cost to government health care programs.

The staggering numbers, however, don't show the stress and heartache on families.

This year, the Post-Dispatch has written a series of stories about Lonni Schicker, 64, and her son and caregiver, Dan Schicker, 32, as they struggle with the confusing, overwhelming and life-changing start to memory problems. The series — Stolen Future — sheds light on the need for better diagnostic tools, care and support — while showing the Schickers finding joy and preparing for what is to come.

For this sixth and final part in the series, other families who have experienced dementia are sharing their stories.

KMOX radio host Carol Daniel knows the importance of sharing these experiences. Her mother was diagnosed with dementia three years ago, and Daniel's father is her caregiver. This year, Daniel was the emcee for the annual fundraising gala for the Alzheimer's Association Greater Missouri Chapter.

“We all have stories,” Daniel told the crowd. “They should fuel this fight.”

Advertisement

‘Do I go this way?’

The week before Christmas, two deacons from West Side Missionary Baptist Church stop by the home in University City where Barbara Lewis, 88, has lived for the past 53 years.

Barbara Lewis rests a moment in her University City home on Wednesday, Dec. 19, 2018. Lewis, 88, learned from her doctor two years ago that she has dementia. She has an appointment with a neurologist next month for testing to determine the cause. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

They visit members who are “shut-ins” and no longer able to make it to church. They stay for an hour, chatting about past reverends: ones who were there when she was baptized, got married, put her parents to rest. Before the men leave, they give her an envelope.

“They gave me a card,” Lewis says moments later. “I don't know what's in it, actually.”

She searches the pockets of the cardigan in her lap, turns it over, and searches the pockets again.

“You put it in your purse, Mom,” says her daughter, Rosalyn Stiles, 64. Stiles has lived with Lewis since her own husband died 11 years ago.

Stiles opens the envelope and counts money inside: $75. Lewis knows right away what she will do with it.

“I had a talk with the Holy Spirit, and I said, 'I have a little grandson who needs a pair of shoes,'” she says. “I have these funny things happening to me, like somebody really talking to me.”

Lewis has an 11-year-old great-grandson who is growing fast and always active. She had noticed a hole in the toe of his shoe.

“He took the place of my younger daughter. Every time I turned around, she ran out of her shoes,” Lewis said. “She was always stomping around on the Ferris wheel.”

Barbara Lewis, (left), talks on the phone with her son on Wednesday, Dec. 19, 2018, as her daughter, Rosalyn Stiles, (right), dodges a walker in the doorway in their University City home. Lewis' memory problems began four years ago. She found the sermons at her church confusing, left ingredients out of her pies and cakes, and thought people were moving her things. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“You mean the merry-go-round,” Stiles gently corrects her.

Lewis' forgetfulness started about four years ago, Stiles says. She insisted people had moved things. The church sermons were confusing. She left ingredients out of her pies and cakes. She got her bank account number confused with her Social Security number.

“I want to work as hard as I can possible to do it, to see if I can turn it around or keep it from getting worse.”

Two years ago, her primary care doctor confirmed Lewis has dementia. She's meeting with a neurologist next month for more extensive testing to determine the cause.

“Hopefully, the doctor will come up with the words for the exact condition I am,” she says. “I want to work as hard as I can possible to do it, to see if I can turn it around or keep it from getting worse.”

Lewis has quit driving. And she's quit what she has always been so good at: cooking.

“Before Thanksgiving, I tried to make a sweet potato pie, and I made the biggest mess,” she says. “When I have to add a lot of different seasons, I get confused. I stand in the middle of the kitchen floor, and I think, do I go this way or that way?”

Advertisement

Symptoms will worsen

Dementia is a collection of symptoms that occur when the brain regions that control thinking begin to deteriorate because of disease. The symptoms are severe enough to prevent a person from carrying out daily activities.

“All of this begins gradually, and it's hard to know for certain whether memory or thinking are declining, but it always gets worse,” said Dr. John Morris, director of the Knight Alzheimer's Disease Research Center at Washington University School of Medicine. “With time, there will be continued deterioration.”

About 75 percent of dementia is caused by Alzheimer's disease, marked by the buildup of plaques. Other brain disorders also cause dementia, including stroke, frontotemporal dementia and Lewy body disease.

Dementia-like symptoms also can be caused by dozens of reversible conditions such as depression, drug interactions and thyroid problems.

Often, the causes can be mixed.

“The end stage will require total care. The person won't be able to do anything.”

Dementia is progressive and fatal. It is a long goodbye. People tend to live about 10 years after diagnosis, Morris said.

What starts out as repetitive questions, miscalculating numbers, leaving out ingredients and minor fender-benders evolves into no longer working, paying bills, cooking or driving.

Patients can become irritable, angry or paranoid.

Eventually, even figuring out how to dress, comb their hair, brush their teeth or go to the bathroom becomes impossible. “The end stage will require total care,” Morris said. “The person won't be able to do anything.”

Advances are unfolding in accurately diagnosing, treating and even preventing dementia. Researchers are studying how to harness the power of the immune system and use drugs to delay the start of brain deterioration, which they have learned begins 20 years before the symptoms of dementia appear.

This year, Congress approved the largest-ever funding increase — $425 million — for Alzheimer's and dementia research. The increase brings the total annual funding to $2.3 billion, up from just $448 million seven years ago.

“We have to invest in these research studies and diagnostic tools to be able to one day say we have something to stop Alzheimer's disease,” Morris said, “or else it's going to overwhelm our health system.”

Advertisement

‘I had no clue’

As Mary and Ron Nicoletti walk out of the dementia wing into the common areas of Garden View Care Center, they pass a large glass enclosure full of small, colorful birds.

“Want to look at birds for a little bit?” Mary says.

Ron keeps shuffling down the hall, eyes forward. “No? OK,” Mary answers for him. “We can just be together.”

They started dating when she was 15½ years old, breaking her no-dating-before-16 rule because her parents liked Ron.

"We're a team, right?" Mary Nicoletti, 66, asks Ron, 68, her husband of 45 years, as she visits him at a skilled nursing facility in Valley Park on Thursday, Dec. 13, 2018. "Right," he responds. Ron, who has early onset Alzheimer's, is now unable to say more than a few words, but generally responds to this one. The couple had so many retirement plans. “We always thought we would have time later,” Mary says. Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Mary went to Cor Jesu Academy and and Ron went to Christian Brothers College high school, but they were in the same parish, Our Lady of Providence, in south St. Louis County.

They continued dating in college, while Ron went to St. Louis University, and she attended Fontbonne University. They got married the summer before their senior year.

“We were one,” Mary says. “There's no one I like better than him. He's my guy.”

Ron worked 22 years in human resources for Anheuser-Busch before becoming the director of human resources for St. Louis Community College. “He loved to help people get jobs,” Mary says. He loved to play the guitar.

Mary's work was taking care of their five boys. She and Ron were avid Cardinal fans. “That's what we did together,” she says. “We had season tickets for years.”

Ron was diagnosed with Alzheimer's eight years ago at age 60. Mary says symptoms started about four years before that, but she did not understand what was happening at the time.

“I just thought he wasn't paying attention to us; and here he was very sick, and I had no clue.”

“I was just ignorant,” she says. “I had no idea that someone at that age could have problems mentally.”

He was spending long hours at work, struggling to keep up. He was not paying bills, blaming accounting mistakes on everyone else. Mary was hurt.

“I thought he was so busy at work, and he was ignoring his family,” Mary says. “He had an MBA in finance. I just thought he wasn't paying attention to us; and here he was very sick, and I had no clue.”

His boss's concerns led Ron to seek help. First, he was tested for depression. Six months later, doctors confirmed Alzheimer's.

Ron had made so many accounting mistakes that he lost their dream home in Tapawingo golfing community surrounding the golf course in Sunset Hills.

“We had a big house. We had everything,” Mary says, “and it all went kaput."

Advertisement

Trying to bring joy

Lewis' husband, an Army veteran and electrician, died 36 years ago. She has five children, including three daughters who live in the St. Louis area. All three try to keep her as involved as possible.

Carlotta Lewis, 65, includes her mom in her event-planning duties — arranging flowers or folding napkins. Paula White, 59, brings her dog for visits. Lewis goes to a senior center for activities three times a week, and sometimes plays bingo, even if it's just one card.

They patiently play her favorite card game, bid whist, laughing through her mistakes.

Barbara Lewis, (right) shares a laugh with her daughters, Rosalyn Stiles, (left), and Paula White on Wednesday, Dec. 19, 2018, as they have her sign her name to Christmas cards in her University City home. Lewis, 88, has dementia and she worries about being a burden on her children. “We try to bring joy in her life," Stiles says. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“We do whatever she wants,” Stiles says. “We try to bring joy in her life and be creative with her.”

The elder Lewis says her children have talked to her about her wishes. “Do I want to continue to live in the house or self-service, or that's not the word … assisted living,” she says. “I'd like to stay in my house; but every time I turn around, something is falling apart or needs to be repaired, and I don't want to deal with that.”

A few weeks ago, Lewis was briefly home alone when she thought men were in her house. They were cussing, kicking in walls and preparing for a gunfight. She called the police and walked with her walker to a longtime neighbor's house. Her family thinks maybe she thought a television show was real.

As she sits at her dining room table with Carlotta Lewis, peeling price tags off charger plates, she tells her daughter that she can't stand the thought of her children being handicapped by her.

“I am not interested in what is best for me but what is best for my family,” she says. “They are all getting up there in age too, and they need to enjoy life to the fullest.”

Carlotta Lewis takes a plate from her mom.

“We are. We have,” she tells her. “Part of our joy is seeing you get what you need.”

Advertisement

Like sand

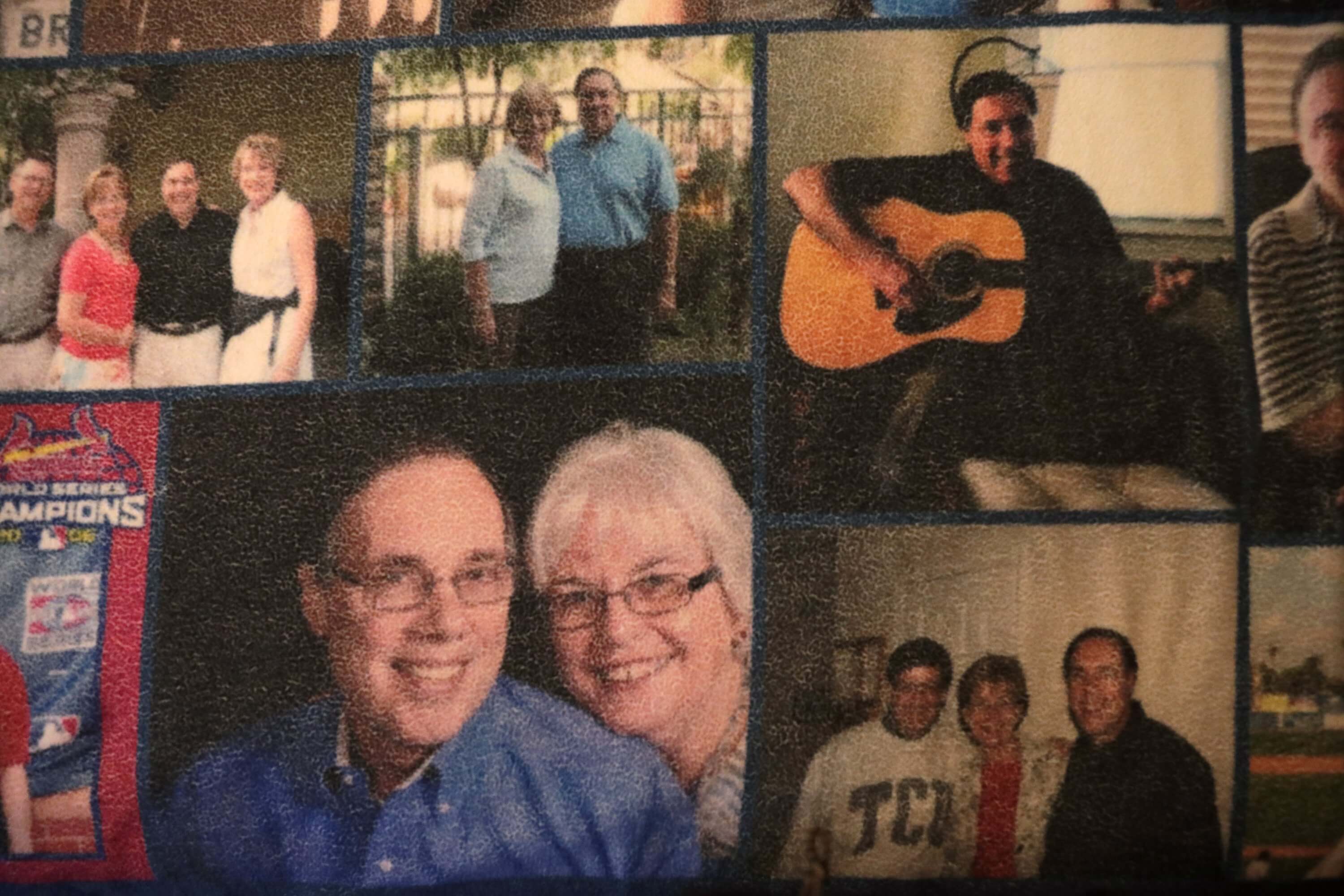

A blanket printed with family photos of Ron Nicoletti with family and friends lays across Nicoletti's bed at a skilled nursing facility in Valley Park on Thursday, Dec. 13, 2018. Ron was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer's at age 60. His wife, Mary, visits almost every day. Photo courtesy of the Nicoletti family

After losing their home, the Nicolettis rented a small house, but even that became too expensive. Mary is thankful that Ron's brother, the executor of their mother's trust, let them live in her house in Affton — the house Ron grew up in.

Two years ago, when it became impossible for Mary to care for Ron, she placed him in a skilled nursing facility. He had to move from that facility into Garden View when a urinary tract infection caused him to act aggressively, Mary said. He has to have a private room.

Using his two pensions, retirement savings and her mother's inheritance, Mary pays $317 a day for the room.

She could apply for Medicaid, the government health program for the poor, but that means Ron probably would have to move to another facility. She worries about spending their savings.

“I could live 20 more years,” she says. “I don't know what I'll do.”

They had all kinds of retirement plans, especially because their first child came just over a year after they got married.

“He wanted to go to Sicily to walk the streets his grandparents walked,” she says. “We always thought we would have time later.”

This year, Mary went through surgery and treatment for breast cancer. She had a gallbladder attack. She couldn't even tell her husband.

“He wanted to go to Sicily to walk the streets his grandparents walked. We always thought we would have time later.”

Mary visits Ron nearly every day. She lives for the moments when he grins, when he seems to recognize her.

After passing the bird enclosure, they head to the administrative offices. The chairs and desks used to spark something in Ron. He enjoyed checking on the employees, like he was back to his corporate self. Today, though, he is quiet.

“Ron, are you tired?” Mary asks, but gets no response. He nods when an employee offers some chocolates, but he just stares at them when she opens the box.

“It's like holding sand and watching it go through your fingers,” Mary says. “I know I'm losing the battle to hold on to him.”

Some people tell her she shouldn't bother coming any more.

“But he knows when I'm here,” Mary says. “He knows he's loved.”

Mary Nicoletti, 66, visits Ron, 68, her husband of 45 years, at a skilled nursing facility in Valley Park on Thursday, Dec. 13, 2018. Ron was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer's when he was 60 and his problems probably started four years before that, his wife says. “I was just ignorant,” she says. “I had no idea that someone at that age could have problems mentally.” Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Questions

We're interested in hearing from readers who are living with dementia, or caring for someone with dementia. As with any conversation, keep comments polite and refrain from personal insults, foul language or off-topic remarks.

Read more about our commenting guidelines.

About this series

Michele Munz has been a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for 20 years, the past nine covering health and medicine. As a health reporter, Munz has won awards for her coverage of midwifery care, an experimental treatment for ALS and the opioid epidemic. She was the St. Louis Newspaper Guild’s 2015 Terry Hughes Award winner.

Christian Gooden has been with the Post-Dispatch since 1999. He is a native of University City and graduate of Cardinal Ritter College Preparatory High School. He earned a degree in journalism from Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga. He has worked at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Milledgeville (Georgia) Union-Recorder.

Cristina M. Fletes is a staff photographer and videographer at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. She received a bachelor of fine arts degree in studio art from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and a master's degree in photojournalism from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Andrew Nguyen

Developer

Josh Renaud

Developer

Beth O'Malley

Audience engagement

Elaine Vydra

Audience engagement

Janelle O'Dea

Data reporter

Hillary Levin

Multimedia producer

Gary Hairlson

Multimedia director

Jean Buchanan

Projects editor

Evan Hill

Print designer

Jennie Crabbe

Copy editor

June Heath

Copy editor

Colleen Schrappen

Copy editor