Stolen Future: Part 5

When I can't take care of her

About the series

Lonni Schicker, 64, was always the one to depend on, to get things done and to figure things out. She was the person who took care of others. At least until about five years ago, when Lonni's doctor told her that at age 59 she had mild cognitive impairment. The diagnosis placed her at higher risk of dementia. Lonni quit her job as a professor and moved into an apartment in Fenton with her son. Her problems have since gotten worse. Hoping to help others, Lonni is sharing her story about her frustrating search for a diagnosis and unique challenges when symptoms strike at a younger age.

Listen

Michele Munz reads the fifth story in her series about Lonni Schicker and her struggles with dementia. It explores her relationship with her son and caregiver, and how they cope with change together.

In a far corner of the covered patio at Seamus McDaniel's, a small crew of people hang pennants, paper pinwheels and shiny spirals — all purple, the color for Alzheimer's awareness.

The decorations sway in a gentle breeze from the open windows and sparkle in the bright, fall sun.

The friends nervously fuss over where to hang the remaining trimmings. But Dan Schicker, 32, is calm and happy.

“She's not even going to pay attention to the decorations,” Dan says. “She's just going to see everyone and cry.”

It is Sept. 29, his mom's 64th birthday.

Lonni Schicker laughs next to her son, Dan Schicker, as he recounts to friends and family how he successfully pulled off a surprise birthday party at Seamus McDaniel's on Saturday, Sept. 29, 2018. He says he wanted to make it a surprise because she gets anxious when she knows a big event is coming up. Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Cake for Lonni Schicker at a surprise party for her 64th birthday at Seamus McDaniel's on Saturday, Sept. 29, 2018. Lonni thought she was meeting her son for dinner. Instead she walked in to fine a surprise party in her honor. Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Lonni Schicker thinks her son is helping some friends move and that he is going to meet her at the Dogtown neighborhood pub for dinner.

But really, Dan went shopping at Party City and stopped at McArthur's bakery, where they wrote “Happy birthday Lonni” in yellow icing across a vanilla sheet cake with chocolate frosting.

Dan has been planning the party since May, when he sent out invitations on Facebook. He's not one to plan ahead, let alone months in advance. But his mom's dementia has forced to him to deal with the future. To think about others. To grow up.

Lonni had to quit working as a professor almost five years ago when she began having symptoms and was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment. She moved in with Dan in his Fenton apartment. He has cared for her as medical bills drained her savings and her health worsened.

Lonni was finally diagnosed with dementia in April. Her neurologist wants to see her every six months.

While Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of progressive forms of dementia, Lonni's neurologist suspected an equally devastating culprit — Lewy body dementia. It is also marked by loss of balance and hallucinations, which she experiences.

Before leaving her job, Lonni was confident, intelligent and a source of strength for many. Now she's feeble, confused and dependent. She can no longer drive and needs a walker or cane. She can't manage her money. She needs constant assurances and reminders.

“With her memory, and the way her body has been deteriorating. I didn't know how many opportunities we would have.”

Dan wanted to throw his mom a surprise party because her anticipation of big events tends to turn into anxiety. She worries about what could happen, what might not happen, who will be there, who won't be there.

“When she gets fixated or set on something, she gets disappointed when it doesn't go right,” Dan says. A surprise party will allow her to enjoy the moment.

He has been forced to think about where his mom might be in a year. Just weeks before her party, a fall led to a back surgery, which led to other complications.

“With her memory, and the way her body has been deteriorating,” he says, “I didn't know how many opportunities we would have.”

Advertisement

Lonni was his rock

As a single mom, Lonni Schicker doted on her son, Dan, as he grew up. "At the end of the day it's always been Dan and I against the world," she said. Now, as Lonni’s dementia worsens, their roles are reversing. (Cristina M. Fletes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

It's always been Dan and Lonni. “My dad bolted when my mom was pregnant,” Dan said.

He was a hard kid. They lived in the Dutchtown neighborhood in south St. Louis, where Dan attended what was then Cleveland High School. He was always drinking and getting in fights.

“I almost dropped out twice,” he said.

All the while, Lonni was his rock. She gave him the freedom to learn from his mistakes and assurance that she would always be there for him.

Everyone hung out at his house because of her. She cared about his friends without judgment. She even took in a couple of Dan's friends with unstable homes. They still consider her their mom.

“She's always been a lover and a protector,” Dan said. “That's always been her thing.”

Lonni and Dan Schicker work out a computer issue in the apartment they share in Fenton on Monday, July 30, 2018. Lonni, who has dementia, says she worries that Dan is caring for her out of guilt. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Dan watched how hard his mom worked. After earning a nursing certificate, she earned a bachelor's and advanced degrees while working multiple jobs as a nurse in hospitals, homes and on call during shows at the Fox Theatre. She must have struggled, but he never felt it.

Everyone in their family turned to her for guidance and help.

“I wasn't the greatest kid, but I always had complete respect for my mother … ,” Dan said. “To see how strong she was in handling those situations made me want to be more like that.”

Midway through high school, Dan knew he was too easily swayed by friends. He was going down the wrong path.

On his own, he enrolled at South County Technical High School, where he ended up graduating. “Without her always trying to influence me to make the right choices,” Dan said, “I would've ended up in jail or worse.”

When Lonni had to quit her job as professor in health care administration at the University of Minnesota because of her memory problems, Dan didn't think twice about her living with him.

“She's taken care of me my whole life,” he said. “The least I can do for my mother is take care of her.”

Dan was happy playing Dungeons & Dragons, drinking and watching ballgames with friends. Now he's had to focus more on his career and figure out how to navigate a complex disease, pay medical bills and prepare for an unexpected future.

“I didn't feel like I was in a place to be able to take care of another human being.”

“I didn't feel like I was in a place to be able to take care of another human being,” he said.

But he's figured things out. He's learned how to talk his mother out of irrational thoughts and fears — while coming to grips with the fact that sometimes he can't.

"He loves cheese," says Dan Schicker as he spoils Harry, the family dog, on Monday, July 30, 2018, before having a meal with his mother, Lonni Schicker. Lonni moved in with Dan after she was forced to quit her job as a professor because of cognitive issues. She was diagnosed with dementia in April. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“I feel helpless a lot because I just can't fix it,” he said.

Lonni feels like she's ruining her son's life. She fears Dan is caring for her out of guilt.

Dan continually has to convince her that he wants to care for her, to stop worrying about him. “It's never been a burden,” he said. “It's my mom.”

Dan tends to take life one day at a time and not worry about the what ifs: What if it becomes too dangerous for her to be alone while he's at work? What if she becomes too weak? What if she does not remember who he is?

“It's hard for me to give up control. People can't take care of my mom like I can. I know how to calm her down. I know how she is,” he said.

And, he deadpans, “You know, I'm just not ready to make my own dinners."

When Dan is stressed, he tends to make jokes.

He imagines convincing his mom she's Wonder Woman: “I can't wait until it gets to the point where I can put a superhero costume in the bathroom, and see her go out and try to save the world.”

Advertisement

Going to be fine

Lonni had back surgery Sept. 4. She needed a spinal fusion because of lower back problems worsened by her falls, a symptom of her dementia.

After surgery, Lonni went into a rehab facility where the incision became infected. She had to return to the hospital for another surgery to clean the wound, which meant another hospital stay and possibly more time in rehab.

The night before Lonni's second surgery, Dan takes her a bag of clothes and other items. The previous day, Lonni had texted him at least 50 times: She was in pain. She wasn't getting her medications. Her bandages needed to be changed. Her IV needed to be cleaned.

Dan walks into her dim hospital room and kisses her on the forehead.

“You are going to get better care. You are going to get your meds, and you are going to be out of here in three days,” he assures her. “It's all going to be fine.”

A nurse comes to check her wound. Dan lets the nurse know a bloody piece of gauze fell on the floor. “I don't do blood,” he jokes.

Lonni Schicker takes a seat in the waiting room on Tuesday, Nov. 1, 2018, before a followup visit with her neurologist at Mercy Hospital St. Louis. Twice while she is waiting, she asks her son what the date is. She says her short-term memory has worsened and her hands shake more. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Dan tells Lonni he ordered what she put in his Amazon cart: a Fit Bit, a cross-body purse she wants to hold her cellphone and lipstick, and a reacher with suction cups. “You can grab cups, you can grab anything you need,” he says.

She wants the Fit Bit because it says the day of the week, she explains. “I keep forgetting what day it is.”

“My scooter will be here tomorrow,” she says, beaming, thinking of how her friends pitched in to buy her a small motorized wheelchair.

“No, Friday,” Dan reminds her.

Lonni insists on seeing her sister, Mary Allen, who lives in the Las Vegas area, as soon as she can.

“We can figure that out when the time comes,” Dan promises.

He checks the messages on his phone: Praying for you bro. Sending prayers. “All these people are praying,” he tells his mom.

“That's nice,” she says, her eyes getting heavy.

“And I'm getting out of here because you are falling asleep,” he says. She apologizes.

Dan turns on her fan, plugs in her phone, puts a bag of M&M's on her tray and rolls it close. He bends down, hugs her and says goodbye.

“Bye, honey. I love you,” she answers.

“You're going to have surgery in the morning, and it's all going to be good,” he says, “and you are coming home Saturday.”

Then he jokes, “If someone picks you up.”

Advertisement

Spell world backward

Complications from Lonni's back surgery delayed her six-month appointment with her neurologist several times. Just days after her surprise party, she had to go back into a rehabilitation facility.

She was well enough to leave the facility on Nov. 1 and meet Dan at her appointment with Dr. Mohamed Babiker Tom Bakhit, who goes by Dr. Tom, at Mercy Hospital St. Louis.

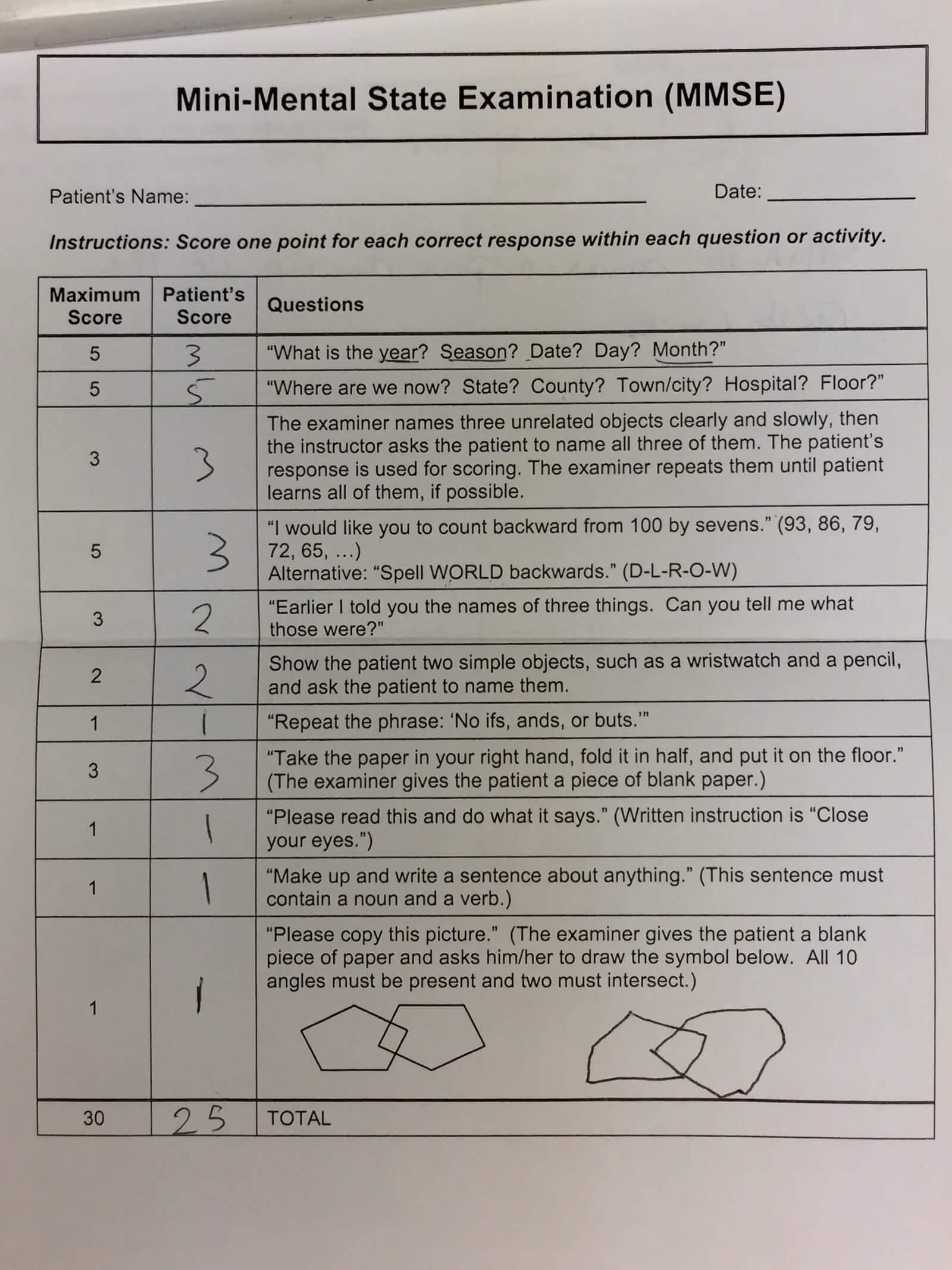

During a visit Nov. 1, 2018, with her neurologist, Lonni performs worse on her memory tests than she did seven months earlier. She's unsure what the date is, although she had asked her son, Dan, about the date twice in the waiting room. "Your symptoms are slowly getting worse," the doctor said after the testing.

“How is your memory?” Tom asks.

Her short-term memory has gotten worse, they explain. She can't remember what day it is. She pauses more as she talks, having to think of the right word.

“Seems like people tell me all the time, 'You already told me that,'" Lonni says. "So I don't ask questions because I'm afraid I already said that."

Her hands shake more, she tells him. “I can drop my phone 30 times.”

Tom asks Lonni what the date is, which she already asked Dan twice while in the waiting room.

“I know we had a Halloween a couple of days ago,” she says. “Eleven four?”

She knows it is November. It's fall. But she thinks it's either Monday or Tuesday. It's Thursday.

Lonni knows the hospital, the city, the county and the state. But she doesn't know what floor they are on.

Tom asks her to spell “world” backward. "D-o-r-l-w," she says. He asks her to count backward from 100 by 7. "93, 76, 69, 52 and 45," she says slowly.

At the start of the appointment, Tom had told her three words to remember: village, heaven and finger. He asks her to recall the words. “Village and finger … I keep thinking 'world,'" she says, "but that was something else.”

Her hallucinations are more frequent, Lonni tells the doctor. She sees animals — like a dog or a rabbit — in her room.

Lonni Schicker is tested by her neurologist, Dr. Mohamed Babiker Tom Bakhit, on Tuesday, Nov. 1, 2018, during a followup visit at Mercy Hospital St. Louis. Her dementia is causing her to lose her balance and fall, and she recently had back surgery because of problems aggravated by her falls. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Tom directs her to close her eyes and touch her nose. Her hands shake as she misses her nose and nearly knocks off her glasses.

“Your symptoms are slowly getting worse,” Tom tells her as he looks at her file.

He brings up Alzheimer's disease — what Lonni suspected when her memory problems first began five years ago.

“It's more clear now that you have a mixed picture,” he says. “You have features that are more consistent with Lewy body; and you have memory and fluency and language issues and even some spatial problems navigating space that is typical for Alzheimer's.”

For the first time, Lonni is prescribed Aricept, which treats confusion caused by Alzheimer's. While there is no cure for Alzheimer's or Lewy body disease, the drug may improve memory and awareness.

Lonni and Dan take the news in stride. They've learned over the past five years that living with dementia is more like a roller coaster than a gradual downhill.

“The problem with this disease is that there are no real definitive answers, and every doctor thinks something different and thinks they know what is going on,” Dan says.

Since receiving permanent disability and finally having a regular neurologist, they trust Tom's prognosis. “He's really the first doctor who has taken the time and invested the time to get to know my mom,” Dan says.

But they realize they've always had their answers. Lonni knows herself. Dan knows his mom.

“At this point, I really don't think about what doctors say because I know what I see on a daily basis,” Dan says. “It doesn't change anything about how we are living our lives.”

Advertisement

Unconditional love

Two days before her surprise party, Lonni is home, wearing a portable wound suctioning device to help her heal after her second back surgery.

Dan tells his mom he is leaving before sunrise to take a call at work, but he returns around 6 a.m. Lonni is asleep in a recliner in their living room.

“My call was canceled,” Dan says. Then he asks an odd question, “Where am I going to sleep tonight?”

In your bed, of course, Lonni answers.

“Well, then where is she going to sleep?” Dan says. Allen walks in.

Dan Schicker brings a plate of food to his mother, Lonni Schicker, before they share a meal together on the couch in their Fenton apartment on Monday, July 30, 2018. The two, as roommates, spend a lot of their time at home watching television. Lonni, who was diagnosed with dementia in April, now is having problems operating the remote control and her phone. Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Lonni bursts into tears. They hug. Lonni won't let go.

“I can't believe you're here! My sister is here! You brought my sister!” Lonni says. “I can't believe you did this.”

On the day of the party, Lonni thinks she is going with her sister to meet Dan for dinner at Seamus McDaniel's.

Dan helps her out of the car and walks her around a corner to the back of the patio. Nearly two dozen guests scream, “Surprise!”

Lonni hugs each person. “I didn't know I had this many friends,” she says, laughing. “Happy birthday!” she repeats to some who greet her.

She joins Dan and his friends in a corner. “How did I do?” Dan asks. “Two big surprises in one weekend!”

His friends tell her how long he has been planning, how nervous he was over keeping it a surprise.

Lonni hushes the crowd.

I want to say thank you so much for being here, she says, "and thanks to my favorite boy.”

She opens gifts — scrapbooking supplies, a tropical-scented candle and gift cards from Hobby Lobby, Ulta Beauty and Walmart. Birthday cards thank her for memories together, and more memories to come.

“I hope she knows how much she is loved,” says June McCartney, 60, of Fenton, who used to care for burn patients with Lonni at the now Mercy Hospital St. Louis. “I hope she knows she's not walking alone. We can't walk it for her, but we can walk it beside her.”

Near the end of the night, Lonni looks to Dan at the next table. “How did you do this? How did you get all these people here without me knowing a thing?” she asks. He shrugs.

Dan never keeps secrets from her. They always tell each other everything.

“I still believe I can care for her but it just seems like this is … I guess I just fear something else could go wrong, and I won't have her home again."

At times when she was struggling in the hospital or feeling down, Dan wanted badly to tell her his plans. To make her feel better in that moment.

But he's become more patient, better at putting himself in others' shoes, he says. “As I've gotten older and had to take care of her, I've grown up a lot.”

His mom's back surgery and complications were a wake-up call.

They had been in a good place. Dan had a new job for an IT service provider that paid more. A friend created a Go Fund Me donation page, which was helping them pay medical bills. They were less stressed, eating better and getting sleep. Dan was saving money for when his mom might need more intensive care.

“I still believe I can care for her, but it just seems like this is … I guess I just fear something else could go wrong, and I won't have her home again,” he says. "This really caught me off guard so much it kind of snapped me into some other type of sensibility.”

At home, Dan installed three small cameras in their living room. He can watch his mom any time from his phone and make sure she is OK.

The cameras also work as two-way microphones, in case Lonni can't use her cellphone. While her cellphone has been her lifeline for keeping her on task, navigating it and the remote control are starting to stump her.

Dan is more strict with her doctors' orders. He's giving in less to her protests.

Lonni is changing too. She's protesting less. She's accepting his help.

“No one has ever really taken care of me,” she says. “I've always taken care of everyone else.”

No one has ever done anything for her just out of kindness, Lonni believes. She fears they expect something in return. Even Dan.

“He wants me to be this person to accept this kindness and love for me, and I've always pushed away from that,” she says. “It's hard for me to accept it for what it is.”

She's realizing that's a sad way to live.

“The person who is teaching me about love the most," she says, "is my kid.”

Dan Schicker says goodbye to his mother, Lonni Schicker, after meeting her at Mercy Hospital St. Louis for an appointment with her neurologist on Tuesday, Nov. 1, 2018. "At this point, I really don't think about what doctors say because I know what I see on a daily basis,” Dan says. “It doesn't change anything about how we are living our lives." Christian Gooden / St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Questions

We're interested in hearing from readers who are living with dementia, or caring for someone with dementia. As with any conversation, keep comments polite and refrain from personal insults, foul language or off-topic remarks.

Read more about our commenting guidelines.

About this series

Michele Munz has been a reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch for 20 years, the past nine covering health and medicine. As a health reporter, Munz has won awards for her coverage of midwifery care, an experimental treatment for ALS and the opioid epidemic. She was the St. Louis Newspaper Guild’s 2015 Terry Hughes Award winner.

Christian Gooden has been with the Post-Dispatch since 1999. He is a native of University City and graduate of Cardinal Ritter College Preparatory High School. He earned a degree in journalism from Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga. He has worked at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Milledgeville (Georgia) Union-Recorder.

Cristina M. Fletes is a staff photographer and videographer at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. She received a bachelor of fine arts degree in studio art from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and a master's degree in photojournalism from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Andrew Nguyen

Developer

Josh Renaud

Developer

Beth O'Malley

Audience engagement

Elaine Vydra

Audience engagement

Janelle O'Dea

Data reporter

Hillary Levin

Multimedia producer

Gary Hairlson

Multimedia director

Jean Buchanan

Projects editor

Evan Hill

Print designer

Jennie Crabbe

Copy editor

June Heath

Copy editor

Colleen Schrappen

Copy editor